An appeal to the Christian public, on the evil and impolicy of the Church engaging in merchandise and setting forth the wrong done to booksellers, and the extravagance, inutility, and evil-working of charity publication societies

| Author | Anonymous |

|---|---|

| Published Date | 1848 |

| Genre | Religious polemic |

| Country | United States |

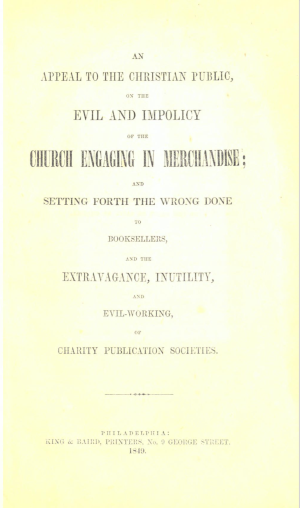

An appeal to the Christian public, on the evil and impolicy of the Church engaging in merchandise and setting forth the wrong done to booksellers, and the extravagance, inutility, and evil-working of charity publication societies is an 1849 anonymously authored work that was printed by King & Baird Printers in Philadelphia.

The book begins with the following quote:

"Labour is the fruit of a spoiled Eden, forbidden still to the touch or taste of charity."

To the Christian public

I have written the following pages with a deep conviction of the truth of the principles which I have stated, as applying to the subject. I have never done any thing for which I am more willing to be solely responsible; but, having commenced without my name, I have thought it most suitable to the modesty I ought to observe, to let it still appear in that form. To the ministers of the Gospel of every name, I would make an earnest appeal. You hold an office greatly and deservedly honoured; but more honoured in its origin than men can honor it. These Societies have your favor, and could not long exist without it. You speak for them. I ask you to consider the case, and what I have stated. It is certain that the public pays more for what charity does than the same would cost when produced by individual means and enterprise; and that it is, therefore, a bad economy of sacred funds. It is certain that such use of these funds does a wrong to individuals engaged in this branch of business, and drives a large amount of capital out of it, and causes it to be invested in publishing injurious books. This is a great and growing evil. Far too many religious books and children’s books are published by these societies. This results from their competition to do business. They encroach upon each other. For instance, the Tract Society, in her zeal to do all things, publishes a class of juvenile and illustrated books, which are fast supplying the field of the American Sunday School Union. The former, so far as the interests of religion are concerned, does more than enough in this department. But I will add no more here, but simply ask every reader candidly to consider what I have to say. If there is truth in it, if the wrongs and evils, which I here proclaim, are half true, let these societies go; let them perish as expedients that have been tried till they are no longer useful; till the principle on which they rest is known to be evil, and to be working evil more and more.

American Tract Society

This institution is called a Tract Society, and, as such societies are apt to do, has been tempted in its strength to depart from its design and become a large book-publishing concern, one of the largest in our country. It professes to furnish religious books at cost, and perhaps when the expenses of its 400 colporteurs and the large salaries of its many agents and clerks are reckoned into the account, this may be found true. Its publications are certainly sold so near their cost that all private enterprise and capital must fail in any attempt to publish at similar rates. Here, then, is a society with its many hundreds of agents and servants, with mouth so large that nothing can fill it, and with tongues so various and many-tined, that you can hear nothing else, crying to be supported on the charity of Christian people, and yet doing nothing to support itself. Its hired emissaries, its devouring presses, are fed at the hand of charity⏤a weak, ill-judging, yet generous charity. Well what is the result? It has paralyzed the enterprise of individuals lawfully engaged in publishing religious and useful books. It has, to an extent many times exceeding the means and influence of society, driven the capital of publishers into new channels, and caused, directory and indirectly, the circulation in cheap forms of more useless and injurious books than the society, with her thousand hands and tongues and charity boxes, can ever counteract. This is no idle and unmeaning view of the case. Every bookseller knows the danger and impolicy of publishing, or keeping on his shelves, religious books. The entire book business has undergone a change. Wholesale dealers, who supplied country booksellers, seldom got an order, five years ago, which did not include many religious books. Now it is a rare thing that a single book a religious kind is called for by houses that formerly sold thousands. They say they cannot sell them, that the demand has ceased. This is known to be true through the whole country, as a change in the times. They can now only sell school books, novels, picture books, and standard books, and none others pay for publishing. This is the general statement of men engaged in the trade. It is caused by the action of religious societies, and most of all by this book making tract society. Wherever they can sell a book they send a man with it, and when he takes pay for it, he asks for a donation, if there is any appearance of ability to give it. Thus, he puts in and takes out, always taking more than he gives, if he can. Well, this method supplies every family that can be reached with a few religious books, and fleeces it of what charity it can, and, as religious books are not necessaries of life, what is gotten in this way, supplies and satisfies, so that there is seldom a call on booksellers, and if they should happen to be called on, unless the desired book is at the society’s low rate, it is declined, or bought with a conviction that an exorbitant price has been charged. This, then, is a brief sketch of the society’s influence. But the say, you show that we make books cheap and are very diligent in circulating them. Is not that a good? What care we for the booksellers? Well, booksellers don’t want your care, but they would like you to have sense as well as religion. That is all. But what sense is there in your doing by charity what individual enterprise would gladly do, and make books cheaper to the people than you do, if you add to your prices the charities they give you. There is no cheapness in your system but what lies in appearance: it is an expensive system to the public. It taxes the poor as well as the rich. You would take money from the poorest, if you could get it, and you often can, for poverty is generally charitable. You gather apples of thorns. But I would have you know it is a waste of Christian charity that is spent on you. If you used the economy that good men should, if you did not try to do more than a prudent business sagacity dictates, if you charged the prices for books by which industry can thrive and be rewarded, now that you are made so great, every stream of charity might turn from you to other and more legitimate ends, and you be left with means enough to do a great and successful business. And if, to what you might do in that case, you add what others would do in the same case, and in a fair field of competition, more religious books would be read and published than now are, and an amount of capital, a thousand-fold greater than yours, would be turned from catering to the corrupt appetite of the people, to spreading useful and religious knowledge. I think your vocation, as you have turned it into book-making, is a bald superfluity; and if I could convince the religious public of it, I should think I had done a great good. There are objects enough, every one knows, of more needful charity than you are. You may call your vocation preaching, but I do not. God has instituted a Church and Ministry to convert the world and keep up a knowledge of himself, and if the charity that is given you were expended in educating ministers to proclaim the word; in building churches and attracting people to them; in supporting missionaries and pastors, many of whom are labouring with constitutions broken, and minds enfeebled by the cares and griefs of an inadequate support, I think that the skies over us would brighten in approbation of the change. How many poor shepherds of Christ’s flock are there, who hunger for bread, who cannot buy a book to replenish their exhausted minds, whose ministry is made feeble and unproductive by causes like these; who might speak living tracts, if fed each with a moiety of the charity you claim.

What business have Christians to give their charity to do that which business enterprise and capital would do, if let alone, quite as well and cheaply? None at all, till it can be shown that there are no neglected and more useful channels for their charity to run in. It is bad economy to do anything with the funds of charity which ready and unemployed hands would do with their own means. But does anyone suppose that a demand for religious books would be unsupplied? No. The coffers of infidelity itself would be readily opened to supply the want. Should we not employ the unsanctified talent and wealth of men for such an object? Of course we should when we can. It is a weak, a stupid, though it may be a well meaning, charity which would do any work of this kind. This society furnishes the Church no books which she does not pay more for than the same would cost if she left book-publishing to take its own course. Men are not justly called upon to aid this society. It should stand in its own strength, and live by its own business, or not at all. It does nothing, when it goes out of its own sphere, as it has, which the Church needs, and it is an abuse to ask the religious public to sustain it. It is an abuse, because such misdirected charity drives a great amount of funds out of the service of religion and turns it against the wellbeing of society.*

* A bookseller, who had published a Bible and several other religious books, turned of late to publishing books of murders, of robbers, and criminal calendars generally; and when remonstrated with, he said, the charity societies had destroyed the value of his better books; he could not sell them, and he must do something to support his family, and protect his property invested. He could not change to any other business, nor could he live on the crumbs that fall from these charity tables. This is one of many instances of a similar character. These societies are destroying all the smaller publishers, and driving them into such expedients and shifts for a living. It is a natural result, and shows conclusively that charity has no right to undertake a business of the kind, and, in fact, any business but such as no labour can live by. It can only do so on the principle of doing evil that good may come. Without the aid of this Jesuitical principle, no charity publication society can be defended. They injure and ruin men in the same line of business, and they care not for it because of some good they have in view. This is but acting out the principle.

Yet the agents of this begging institution will tell the people, you must give us money to publish good books to counteract the influence of bad ones, now so numerous, when it is the policy and agency of the society which has so multiplied bad books of late years. It is a common sentiment of booksellers, that this is the fact; and I trust I have made it sufficiently apparent, by exhibiting the false and injurious principles on which the business of this institution is conducted.

Apply the same principles to any other branch of business, and it would and must ruin it. Suppose you get up a great charity-box and call it a work-shop, and have apartments for various arts, and say, we will supply the poor and rich at cost; I reckon we could get agents enough to work in it, by paying them well,who would be very zealous in calling it a benevolent and useful institution; and if the public chose to supply its demands in this way, it would soon be the ruin of all engaged in the same business. Is there any more legitimate branch of business than that of publishing and selling useful books, and is there so little that we can do with our charity, or have we so much of it, that we must drive every man with his means from the field? When will good people see the folly of establishing any such publishing concern without requiring it after a fair start to support itself by the sale, at proper business prices, of what it produces, giving away only of its acquired ability? This is the only live and let live principle that can apply to the subject, and I will add, the only just and sensible principle that can apply to it. I might extend the application of these principles, and show their injurious action, show that they all and us in evil and folly by means of our own charity. Our charity is a talent that is to be improved wisely, or not at all. Any thing that touches the motives of human industry, to weaken them; any thing that charity does that would be done if she let it alone, is a positive evil, and the law which makes it so, is written by the finger of God, and we are bound to see its characters in his word, yea, sinking into the very flesh of our nature.

The following propositions and statements are considered incontrovertible

1st. That it is wrong in any case for charity to undertake a work which there is a sufficient motive for labour to perform. That its only legitimate sphere is in doing what would not be done if she let it alone. That all charity publication societies, tried by this rule, must fall to the ground. That, however useful they might have been at first, they are no longer so; but are wronging men in the same line of business, and doing a work with more expense to the public, than it would cost to do it in any other way. It does not help the case at all, that reasonable prices are charged for the products of these societies. When this is the case, the buyer and charity both give certain prices for a book, which put together, make it cost more than it would if produced by private labour and capital, and that by all charity has paid in the case. This single illustration shows that it can never be consistent with public economy to employ charity in this way. I admit, indeed, that charity may properly be employed in circulating religious books; and even if the Tract Society had confined itself to publishing tracts, as these are matters to be given away, and require much particularity of attention in producing them, there would have been no ground of complaint; but this and other societies have departed from their design and attempted to do everything. They have so trumpeted their usefulness, that good people, not considering or understanding what they were doing and its effects, have given them money freely to work with. Thus they have advanced, till they have become a monstrous expense to the public, and are working the ruin of thousands, connected with the trade, who would do all this work cheaper, provided charity would do what it now does to circulate the books. Take the interest of the money that the Tract Society has invested in real estate and otherwise, and that alone would meet the expense of circulating more books than the society now does, and the church be saved all expense for agents and colporteurs. Can sensible men look at facts like these, and feel that there is any propriety in continuing such an institution?

2nd. This and similar institutions are doing more harm in their tendency to discourage the higher grades of authorship, insacral literature, than any good they can accomplish. If an author will write a light work, fiction, a saleable book, a bitter sectarian book, he may find some charity that will publish it and pay him something for it: but no great or catholic work will they touch; and they create and feed distaste for reading such works; they impoverish regular publisher, and dishearten them about undertaking such works. If a clergyman would publish a volume of discourses, or any work of great learning, he would not think of going to these societies to publish it, and they would not take it if he gave it to them. And yet no mind can estimate the influence for good of such productions as are worthy to live. They are the only living links that connect the spirits of one age with another, and keep men in the style of men. What should we have been, if the last age had left us nothing but such issues as come from these societies? The dilutions would have sickened us, and kept us children to the last. We should have had but dribbles of knowledge, and we might as well have had a library of chips, and studied how they were struck out, whether with one or two blows. I consider the religious authorship of this time killed by clarity, I mean such authorship as will do any good in coming time. The only bait held out is to write to please children or sects, and there are so many hirelings that have capacity for these things,that they swarm upon us in leaves; and a pity it is that they could not be turned to enriching the earth as other leaves are. We could then see some use in this creation of charity. I do not mean to say that respectable books are not written for them; but that they publish a great deal of trash, and that they melt up almost as many sets of stereotype plates in a year, as they make new ones, and thus they go on, wasting the charity of the Church in time, paper, printing, and stereotyping freshworks to share the same fate. Is there any farce like this farce? Would any of these societies have published the works of Presidents Edwards and Dwight? No. And yet their works have done more for mind and religion than all the books they ever have or will publish; and so of many other works that might be named; yet these societies are called about the only agents of good we have in these times; they do anything to raise funds, on the plea of utility; send their traveling agents over the land for this purpose, who get plenty of money, because it is imagined they are doing a good work, when it is only a work of superfluity they do, and this at the expense of men who would do it quite as cheaply, yea, more cheaply, without one cent’s charge to the public. When will men see things as they are? Shame on the inconsideration of those who, if they be honest, must be deluded in preying thus on the pious charity of the public! I have no doubt of the well-meaning of the persons concerned in these efforts, but I have as little doubt of their utter inutility.

The following propositions may be considered as fairly drawn from what I have written on this subject

1st. That it is a perversion of Christian charity to publish books which private enterprise and capital would furnish quite as cheaply.

2d. That the publications of these societies, when all expenses which are paid by charitable contributions are reckoned into the account, cost the religious public more than the same would in any other way of producing them, besides the incidental evil of driving or tempting a large amount, of capital into injurious channels.

3d. That the action of the societies is, therefore, inexpedient.

4th. That charity, given for such an object, is not only wasted, but works a positive evil to the community, by violating every sound principle of political economy.

5th. That every institution of the kind should be conducted on self-supporting principles, and thereby leave a fairfield for competition to individual enterprise.

6th.That the Church has no charity which she can rightfully employ in disregard of these principles.

7th. That charity must be just and sensible, or it degenerates into a mischief-working weakness, not to be reasoned with.

8th. That when this institution, or anyone acting in the name of charity, and for the public good, violates the plain principles of morality, as has been often done, by publishing the same books as other publishers, and thereby depreciating, and, in some cases, destroying the value of the property in their hands, it does in the name of the church, and with a religious sanction, what of ends the moral sense of an irreligious world.

Now, what is the estimation in which the claims of a society should be held that publicly disregards all these considerations, and publishes books professedly at cost, and calls on the religious public to pay all its colporteurs and agents, and to foot all its bills?

Men will give only a certain amount of their income in charity, and can it be believed that an institution conducted as this is, can justly claim the large share it receives? I cannot think so, or see how any thoughtful mind can. I have written, as I think, without religious or sectarian prejudice to the society, and with a purpose to express, fearlessly, honest convictions. I have sought to exhibit the principles which are involved in the case. I think I see enough in them to call for public consideration. Let it be shown that this is a legitimate charity as now managed, or let it be abandoned, and let other more needful objects receive the charity of a considerate public. In my previous remarks I have confined my attention mostly to the American Tract Society, because that society openly professes, and manifestly does publish books at cost, and in some instances, I know, no regular publisher could make the same book by the thousand at so low a rate as that society will sell them at retail; and yet from prices that are below cost of making, it will make a discount to sellers of 20 percent. A super abundance of charity enables the society to do this. Thus the Church is furnishing the poor and the rich, and even book-sellers, with books at cost, and even below cost, in some instances. This is very generous, but more stupid than generous. Tried by any principles of reason, justice or public economy, it is ridiculously wrong.

But the principles of reasoning which I have applied to this society, will apply with more or less force to all charity publication societies. This I will show before I have done. They are all wrong in principle and wrong in action. They work wrong because they are wrong in principle.

I think it is wrong for religious charity to engage in any branch of merchandise. If it may engage in one branch on the plea of utility, it may engage in all, for all are useful, and then we should have the spectacle of the Church’s doing all the business of the world. It would then be a secular Church, and its ministers be secular men, as many now are, to a mournful extent, from the multiplicity of cares and duties which publication societies and their committeeships impose on them. The course which things are taking is secularizing the Church and ministry. That is one and no small objection. For this there is nothing in the Bible, or in the practice of the primitive Church, to give the least sanction, but everything against it. It violates every true idea of a Church and ministry as divine institutions.

No far from a million and a half of dollars is given annually in the name of the Church to publish books. Three fourths or more of the entire capital employed in the religious branch of book businesses charity, and the little private capital remaining in it, is fast making its escape as from a burning house. It would open men's eyes to the folly and wrong of this system, if you were to propose that the Church should do all this business and drive all private enterprise and capital out of the field. O no, this will not do, it would be said, and yet these institutions are saddling this business on the Church as fast as possible; and we have the spectacle now of as much competition, as much cupidity, as much ingenuity, as much catering to public taste, as can be found among any class of men engaged in the same branch of business. They are not content to stay in the sphere they were created to move in. They hitch onto their wheels everything they can make money by. They open shops and sell general books, and their plea is, that they must make their expenses, but the plan is a virtual tax on booksellers to pay, so far as they retail other publications than their own, and so far as those profits go, the expenses of these establishments. For example, the American Sunday School Union, though professedly not a Sectarian institution, makes more annually by the sale of the Book of Common Prayer, than any two stores in the city by retailing the same book. It has no proper right as a charity institution so to do, and all that is so made comes out of the booksellers, and goes to support the agents and clerks of the Society. This society too keeps most religious books—is agent for a publishing house in London, and does as much as she can to monopolize the religious book business of the city; and, I say, it is all a tax on the business of the trade, made in the name of charity, and applied in the name of charity to support salaries, and do a charity work in that institution, and so far as it goes, has a tendency to dishearten and drive out of the business of religious bookselling all who are attempting to live by it. The public, too, are taught that when they buy books at the counters of the societies, they are contributing to the treasury of the Lord. This is an enormous fallacy. It goes every cent to enable those institutions to build up large and overawing stores, to give larger salaries, as they do, than any private business can afford. It impoverishes men who give all their time and means to publish and sell books, quite as useful as any that the societies can publish. So far from being a duty or a charity, it makes the rich richer and the poor poorer. It is a principle that would take the bread out of the month of the starving children of men honestly doing all that their time and means will able them to do for the benefit of the community, and give it where it is not needed, or convert it into the outward embroidery of a showy and useless charity. This is the amount of it, and the best that can be made of it. It is no principle; it is a notion got up by the clamour of these institutions for charity; a clamour that would die down and sink to a gentle and rational voice, were it not for the self-interest which the salaried abettors of these institutions have in glorifying them—misunderstanding and misleading the public as to their real utility. There is no utility in them, viewed on a large scale, and estimated by their far-reaching results. Religious charity cannot undertake such a work as this without landing itself in unmitigated wrong doing. Charity thus says you shall not get your living by the sweat of your brow. I will annul this law, but leave you without a living. I will do all the work, and this seems very generous, but then she adds, I intend also to pocket all the profits. It is useful and productive labour, not labour that lives on charity, which charity should both create and foster. I speak strongly, because I am just as well convinced of the in-utility and evil of these institutions, as at present conducted, as I am of any truth that has ever been stated. The Sunday School Union is liable to the same objections in principle that I have made to the Tract Society. Like that, it professes to furnish its publications at cost. It gives away to the amount of its charity receipts, and all the profits it can make on the sale of books, go to support expenses. This is the same as the Tract Society in principle, and as completely shuts out all competition. It is all charity, charity, and no cheapness.

The American Bible Society is liable to the same objections. It is a useless and very expensive institution to the public. I have heard booksellers say they would give that Society $20,000 and take its business, and bind themselves and their heirs in all time to supply the demand for Bibles at the Society’s price, and thus save to the religious public all the charity it expends in making Bibles. I have no doubt Bibles in that case, if purchased in large quantities, as they now are, for gratuitous distribution, would be furnished cheaper than they now are; and so of all religious books which it is desirable to give away or sell at low prices. If Societies were formed as now to purchase and distribute them, and the publishing of them were left to individual enterprise, the price would fall to the lowest living point, and there would be hands and capital enough to engage in producing the matone half they now cost the Church in charity. There can be no doubt of this. Twenty thousand Bibles have been imported the last year, cheaper than they could be bound for here in the same style. There cannot be a demand of this kind which would not be supplied, and the price would fall in proportion to the demand. This is a law of trade ascertain to secure these results, as that two and two make four.

Quarto Bibles are manufactured and sold to the trade in any quantity for seventy-five cents, and this is lower than any of the Society Bibles—it is so low that no person can live by it. Suppose the Bible Society has $200,000 invested in real estate and material for business, and suppose the interest, $12,000, were expended annually in circulating Bibles, leaving the publishing of them to the trade, what a saving of expense it would be to the Church, and Bibles would be as cheap as they are now, and better got up, when left in this way to the competition of the trade.

The American Sunday School Union probably never did and never can make enough on the sale of its own publications to meet its expenses, and hence it has to rob booksellers by undertaking the sale of other books, and using all appliances to invite trade. Its expenses, its salaries, are greater than any private house does or can pay; and if all were charged on the prices of its own books, salaries and expenses must come down, or prices go up to an unendurable height; and hence as they can sell books, booksellers must be, or are taxed, to make up the deficiency. This is the common sense of the case, and I think it would be tameness in me to slate it in any other way, or call it anything but a wrong.

The Presbyterian Board is no better in its effects on the book trade. It is a money making concern, and does nothing which private enterprise would not gladly do cheaper. It has published a number of books on the trade, which is a wrong in principle, and a superfluity in charity. It is making a house of merchandise of that Church, and its ministers seem to glory in the great work they are doing, giving time to it with a zest that quite equals what is ever seen in the walks of trade. They publish books in ornamental style. They cannot find enough that is unpublished to do, but run so fast, that they have declared, as with a view to deter booksellers from publishing any book, that they will not mind it, but will publish any book they choose, no matter who has published it before them. In this they have violated a principle that the worst men in the book trade have generally regarded as sacred, i.e. not to cheapen or ruin the value of property already in the hands of others. It seems to be left to religious charity in her zeal, to take the lead in acting on this principle. If I was to give my version of this, it would be, that the church having gone astray into dealing in merchandise, God has left her to commit follies and wrongs greater than the world is want to commit, that by the baldness and superfluity of her transgression, she might be redeemed from long engaging in the business of this world, and follow that which is more spiritual and more within the design and office of a Church and ministry on earth. It is lawful to make good coats—it is wrong that they should not be well made, but should the Church turn itself into a tailor’s shop, and the ministry set to, to work at that trade in order to secure this result? As well in principle might this be done, as that the Church and ministry should undertake the publication of religious books in this land. The cases do not differ in principle, differ as they may in other respects.

The Baptist Board are going largely into business, and there never was a more useless charity enterprise. I have no doubt that there is a publishing house in Boston and one in this city connected with this denomination, who would take all the property of this Society at a large advance on cost, and furnish the same and all other books as cheaply to the people. The Board could then use their interest and principal in circulating the books, and spare the Church all calls for charity except for this object. But the proposition would not be listened to. It has taken the grip too strongly for money making. These Boards appear to have no sense of justice to the booktrade. If they publish the same book as the trade, they put it down so low as to destroy all competition. A bookseller has a Baptist hymn book; he pays a heavy copy-right for it. This is a property the Board could use to advantage, but there is no way to get at it, except to publish another so altered as not to violate copy-rights, and then put the price down, and use its agents and business clergy to introduce it, and it soon has a monopoly hymn-selling, but precious little moral music is there in it. The Presbyterian Board took their hymn book and Confession of Faith out of the hands of booksellers much after this fashion. It publishes a Pilgrim's Progress with expensive engravings, stereotype plates and all a gift, and it thus is enabled to publish the book lower than it would—still not so low as when the object is to kill at a blow a book before in the hands of others. I cannot but think that if the wrongs and evils of charity work of it, there will be a in the public will understand the best view to be taken which as a moral motion turning about, and in a going the other way, the public mind, would preach like a voice from a better world.

To this date the Episcopal and Roman Catholic Churches have done less in merchandise and trade than any others, calling themselves Churches, and they are the chief support of booksellers. The Episcopal Church has left her Prayer Book and everything to the management of business enterprise, and she gets it as cheap as it can be made, and cheaper than any charity enterprise could furnish it, if it charged all expenses on the book, yet these societies must deal in the tempting morsel left to individual competition, and support themselves by the profit they can make on it. To see an institution, in no sense Episcopal, do this, when its principal supporters and acknowledged influence are sectarian, in the general opinion of that Church, is a sight one is not apt to look for or want to meet with. It thus forces the whole Church into its support whether she will or not. It takes of her fleece as by the way-side and lets her go.

I might go on and instance all the Societies, and find all liable to the same objections in some degree; but it would be little better than a repetition of what I have said. They generate and emulate each other. They are formed in many instances to counteract the influence of each other. They operate to strengthen denominational and sectional prejudices, an evil which all good men must deplore. The Evangelical Knowledge Society sprung up in this soil, its eye caught on what others had done and were doing, and it must do some great thing; it must at first open a store; it must keep clear of booksellers as of breakers; its individual existence must be significant, it must model on and imitate the great boards about it—it could do wonders. Well, what has it done? It has not a simile book, and it a published never will publish book, which any publisher in this land would not have published on his own means and furnished to the Church on its recommendation, without one cent’s cost, the Church engaging to buy the books as she does of the Society, and thus all the cost attending the publication of the books be saved to the Church. In nothing but the business of charity would so obvious an advantage have been disregarded. The same attention could have been given to the character and editing of the books that now is, and the charity of the Church only employed in purchasing if and distributing them as it now is. All these books, could and would, under such an arrangement, be furnished 20 per cent under the prices the Society now charges for them, and the cost of rent, agent and publishing saved into the bargain.

Would any set of men in the use of their own means have disregarded considerations so obviously expedient! Nothing but charity, reckless and blind, could do it; yea, charity bent on some ambitious and useless display of itself. The men that have done this, are men that I highly respect, that I love and confide in as truly as I ever can in any, but I have set out to speak my mind on what I esteem to be as important a subject as any that can occupy the attention of the public.

The following assertions, I consider, carry in themselves the proof of their truth

1st. I say these societies and all they do are a tax on the honest industry of men engaged in the book business. They are wrong in principle; and I say, as they are managed, they do not make books cheap, nor can they make them so. Somebody pays more for them than would be paid if they were produced in the regular way of the trade. I defy any one to show this is not the fact.

2d. I say that in doing this prodigal and expensive work, they drive a large and incalculable amount of capital into injurious channels of publishing, and break down and discourage every man in the business who is restrained by his principles from engaging in publishing, and selling works of doubtful utility.* I say they have done this work already in the name of religious charity; and I think it does show that charity has undertaken work to which it was not called, and which cannot prosper for good. Let the contrary be shown, if possible.

* I say the publications of these Societies are all lower than private enterprise can live by, unless charity should go to the expense of making and supplying a market, as she does for them. This fact I would have borne in mind as one that is doing a great wrong to publishers. They cannot stand by the side of such a system; and still the system is a needless expense to the public, by the whole amount it invests in publishing. With the command the Societies have of the market, booksellers cannot publish at the same prices and live, but having the entire market to themselves, they could do so. None know better than the Charity Societies that they could not publish books, and thrive at their prices, without the aid of charity. What then does charity in the case, but dishearten all private enterprise for good? Nothing else.

3d. Men, generally, who have made fortunes in other branches of business, are called to the management of these institutions; and they thus carve out work for charity to do, which destroys a branch of trade by virtually burdening it with the support of these charity shops. I know one publisher was waited on by a liberal and wealthy merchant, and told if he did not give him a certain quantity of a book he had published at cost, that he might sell it and give the profits to a poor church, he would publish the same book to effect that end. This man did not think of making his own business build up the poor church, but forcibly taxes his poor neighbour’s for it, and so it is with the wealthy managers of the publishing societies. Remember the ewe-lamb in the parable.* They carve out work against another branch of trade which ruins it; and if the same plan had been pursued with regard to that branch of business by which they made their fortunes, they would have had no ability and no time to spare from the support of their families for such an object. The same principle applied to all branches of industry and trade, would soon make a society of poor men, and leave none with ability to give. Does not this view show that there is an equal want of true heart and true policy in the management of these establishments, and that they are perverting the Christianity of our day—making it worldly, selfish, calculating, bustling and business-like? I must say that I can see it in no other light, and I think the bitter fruit of evil will more and more appear. I ask the Christian public to pause and weigh the considerations I have offered. I know there is principle and there is charity in Christian men, and I know that truth must prevail with them at last. Streams of charity must, to be healthful, be fed from springs of industry. Charity, in disturbing these, kills itself.

* A manager in several of these Societies remarked to me, “The Church has a right to do what she pleases with her charity.” I have no doubt this has been a common opinion, and yet there is no reason or justice in it. It is the opinion of a spoilt child—I may, because I will, and rises no higher indignity. The right or wrong of actions must be determined by expediency, by their results for good or evil. We may not do evil that good may come. This is a principle of the Protestant Church at least, and yet its opposite must be acted on when charity obtains a proposed good through the ruin or injury of others. But if mere expediency be the rule of trying these societies, I think I have shown that they are fast resulting in evils of a commanding grade.

4th. I say that these societies, doing business on the treasury of the Lord, pay higher salaries than any private book concerns do or can pay, and that this is the temptation for them, through their agents, to set to so sharply for money making. It is this spirit, this prodigality in expense, which has prompted them to open stores for the retail of general books; to build up large and expensive warehouses; to publish annuals, picture and illustrated books; to bind them up in in the most expensive styles; to vie in all the arts and expenses of the trade. They thus use Christian charity in ornamenting books to bring money, not in publishing cheap religious knowledge, as they were created to do. It is a monstrous abuse of their trust. It is a farce to call this doing service to religion. It is a war on the private enterprise by which charity lives. I say that in these respects and others, these societies have violated their charters—the Tract Society in publishing books—in setting up to supply the country with books, and selling them under cost to the trade—the American Sunday School Union in opening a general religious bookstore, and going into all the arts of manufacturing and selling books—the Presbyterian Board, in following suit, in publishing works of art and ornament, and vieing with the world for trade.* They have thus become money-making, secular concerns, and as charity supports their expenses and bears their losses, no private capital and enterprise can stand up against them. Not one of them could have obtained a charter had this been their avowed aim and policy from the start. They deserve to be discountenanced by all honest men; they must be, by all who are not willing to aid them in preying upon the enterprise and labour of the country. A rich man gives them a set of stereotype plates with engravings, another gives them this, and another that, and thus the capital of one branch of business is employed to destroy another. These men plan and give money to execute the measures that work the ruin of others, and think all the while they are doing God service. They invite the public to patronise these charity institutions, instead of men who give all their time, talents and means to publish books, quite as useful as any these institutions can publish. These last ask no charity, no praise for their work, and nothing but thoughtless inconsideration can induce any right-minded person to give to, or buy of, these societies, in the conceit that they are more meritorious, less selfish. They are doing a good, an equal good with their own means—these societies are only using the charity of others for the same purpose. Which is most to be praised, most to be encouraged by sensible people? Let good sense answer. That is all.

* There is one thing I would have the reader mark, it is that I would not abate the action of religious charity in circulating good books, but have her leave the publishing of them alone to secular enterprise. Let funds be raised as now forth is purpose; let the demand be kept up by charity as it is now, and all good books wanted, would be furnished as cheaply as they are now, and the Church saved at least one-half of her charity. I admit for instance that the publications of the Presbyterian Board are cheaper than booksellers can live by, having to compete in a market supplied by charity at these rates, but if charity would go out of the market, and still keep up an equal demand, then the trade could publish quite as cheaply, and the Church have no part in the first cost of books.

5th. I say that twice as many religious books are published in the country as ought to be, whether we regard the interests of publishers or the interests of religion. No sooner is a good book issued than it is lost sight of indie clater about another, and thus the best books are displaced and little read. As mattering knowledge of each is even more than can be looked for in such a state of things; and these Societies are responsible for this redundancy. The two S. S. Unions publish twice as many books as can be useful. The multiplication of children’s books is the distinguishing folly of the age. It is an injury to the children in the first place, and in the second, it is an abominable waste of sacred funds. But these Societies must do and report a great business; and to please the children and make sales, they must embellish their works with gilt and pictures. Such a variety in their issues is a nuisance, and I believe is doing the children of the country more harm than good. I was once a child ,and I got up to manhood without these helps, and I do not know that it took me longer than it does children now-a-days; but this I know that the reading of such books is all going to make nobody wise. One seed of knowledge planted in the heart, one principle of truth mastered in the mind, is worth more as basis of moral and intellectual growth, than all these societies can do by all their fictions, and stories, and illustrations, a thousand fold more multiplied. A few first books and catechisms, and the societies could, with profit to the rising generation, be excused from doing any more; but they keep the mill grinding, and why? Because they must make money to sustain their expenses. All they make, it is said, goes to meet expenses; and hence if they sell ten instead of fifty thousand dollars worth of books in a year at one-third profit, it will make quite a difference with those who take the profits, and hence this flooding the church and country with juvenile books and those in a costly and saleable style. I know no other rational view of the case, if it is true that these societies do not lay up money and turn it into capital, and it seems to be admitted that they do not. The Methodist book concernn* has a sinking fund for the benefit of the ministry, and it is fast making it a business church, and its ministers book peddlers. The Presbyterian Board** has, or is about, I am told, to adopt the same plan.

* This concern is publishing a new hymn book which it is estimated will be a loss to that community of 200,000. No reason for this can be seen except that private enterprise by publishing in other sections of that body, is taking this business, measurably, out of the control of the concern, and hence this business church and its peddling ministry, must strike a blow which costs a half a million, in order to take all into their hands.

**This Board has hit upon a pretty device to catch custom, in publishing a catalogue of its books, in which it proposes to give fifteen dollars worth of books or nearly at this rate, for every ten dollars worth purchased at a time. None but managers of charity could have thought of such a device, or had the effrontery to put it in execution. Suppose a neighbor had purchased a thousand dollars worth of these books with a view to sell again, and found, that by the action of this measure, he could only sell them at cost, and his time and expense be lost into the bargain. Could he think it an honest institution? Could any bookseller be thought decent in following this example? It would not be honest; it would be a breach of the faith on which all business transactions rest. It would wrong and undo men who depend on retailing their purchases. And yet this is the way these societies and their managers treat booksellers. They take their business out of their hands, cheapen their investments, and are utterly soulless and heartless about it. They do this in the name, and for the cause of religion, when there is not one of them who can say, it is doing to others as they would have others do to them. Where have they learned that they may do collectively what they should not do singly? When have these men reflected on what they are doing, or reflecting on it, found it was consistent with the easiest principles of our Saviour’s teaching? If I had not to deal with religious men, I should not expect to reform them or check them in any profitable or favorite career, but a wrong, an inconsideration like this, shall not go unexposed for want of my asserting it.

Can it be possible that the wise fathers of that church are willing to hold out such a bait to its rising ministry? Instead of teaching them to rely for support on Christian liberality and the favour of Providence, it tempts them to become supporters of an Institution in which they have a selfish interest by becoming shareholders in its profits. It is a shocking perversion of the office and end of the Christian ministry, and the evil effects of it must sooner or later appear. I am willing that my character for wisdom should sink with the failure of this prediction. The wisdom of God’s designs will appear at last, however they may be obscured and flooded over with contrivances of our own. There is more sagacity in faith than in our invention, for well-doing. And if we acted on this truth as a Church, and let publishing and business alone, our wisdom would appear. The ministry would be relieved from many temptations. Their time and sensibility could be more exclusively given to their work, and grateful and improved hearers would quickly attest the change. I am now prepared to offer the opinion that, if the Presbyterian and the Baptist Boards, the Methodist Book Concern, the Episcopal Sunday School Union, the Evangelical Knowledge Society, the American Tract Society,* the American Sunday School Union, the American Bible Society, were all blotted out of existence, and their stereotype plates sunk to the bottom of the sea, the cause of religion and the best welfare of society would not seriously suffer by it. The church’s millions of charity would be saved, and she restored to her scriptural vocation. Books of all descriptions would be as cheap and as plenty as they are now. Industry would be thriving in this branch of trade, and its capital would be vieing to suit the public taste in the style and cheapness of religious books. Sectarianism, stiffened in its back by the moral effect of these associations, so that it will sooner break than bend, would begin to melt away, and religion everywhere be more liberal. It would not appear before the world as if it had been run in some physical mould and was not accountable for its shape, but there would be a sky-openness about it, a largeness of view, in which it would approximate, as it does not now, to the stature of a perfect manhood in Christ Jesus. I now ask the religious public to withhold all their charities from these publishing institutions;** to force them to live by the economical management of their business, as other men do, or fail. This is the only course that can be just to men engaged in the same line of business. You have given them funds to begin with; that was more than your duty: let them now live by their own strength, and you will soon see if they make books cheaper, and learn what you pay for their service. You will earn that the only voice that calls on you for charity is tuned by the profits made in your employ.

*This Society is fast superseding and supplying the office of the S.S. Union, and it has come to that now, if there is any use in either, there is none in both. They are catering for employ in the same field, and I reckon the harvest will be small to one or the other after a little. If there was any propriety in the origin of these Societies, there is none at all in their doing business on so large a scale. Their greatness, their much doing, will be their ruin. Such great bodies will break in upon each other and leave each scrambling to save the pieces.

**It has been said these Societies have capital enough to go on without farther charity from the public, and would do so, if forced to that course. They, no doubt, will die hard, but they could not live, if the public took no more interest in them than it does in private concerns. Their worldly greatness would soon pass away, and that is a chief charm of their existence. Without charity receipts their dead stock, would remain on hand, and prices must go up, or their capital would be quickly consumed in expenses. They would cross each others track and attempt to do each others work, till they would present a moral spectacle of ruin and competition, such as we have not dreamed of in our philosophy. It is also too clear that such an unaided existence would not advance the public good, and would interfere with the rights of private enterprise. They would be still charity institutions, doing business on the funds of the public, and charging the public just as high prices as if they had not received a cent from it. There is no justice, on economy in this. See page 17 for some things which should be refuted or these charities be given up as evils.

A sketch of what should be done

Not a cent more should ever be given to Charity Publication Societies. They should all wind up, and dispose of their property to the best advantage; and the whole amount of their capital should be converted into a fund for the purchase and circulation of religious books, the publishing of them being left to individual enterprise. Books would then be as cheap, if not cheaper, than the Societies make them. Societies might be formed for the execution of these objects. But Charity should invest nothing in producing books. She should not touch the springs and rewards of productive labour. Labour is a fruit of a spoiled Eden, forbidden still to the touch or taste of Charity. All needless expense in ornamenting and illustrating books should be abated. All light and fictitious works should be expelled from the service of religion. They create a false taste, and a distaste for more improving books. Their evil effect extends into the manhood and womanhood of the rising generation, and makes it less reliable, less stable, less self-productive. Because such fictions please children, is no reason why they should have them. Children should be early taught to read and profit by men’s books. Any well written book is simple enough for youth. That much neglected, yet deeply thoughtful work, Watts on the Improvement of the Mind, can be appreciated by any intelligent youth; and once mastered, is worth more informing a character for well doing and well thinking, than all the juvenile books that have been published in the last ten years. This plan, or something like it, adopted, and millions of Charity would be saved to the Church, which she could expand for more appropriate and needful objects; say in the support of Missions in poor and destitute places. Planting a living preacher in such places, building him a church, and leaving with him some of the best books, charity might go on and have no need to return again, resting assured that tilings would be well done without her further help. This would be doing our work according to the Gospel, each and all acting in a proper sphere.

N.B. – Will Christian men recede or persevere when the principle and action of these Societies are shown to be evil? This is the question. Will men use their means and influence to support what they know is working a wrong to others, and is no just economy of public funds? That is another question. Will the managers of these charities hold on in their office when they know they would object to the same course, if it had been applied to their own business? This is another question.